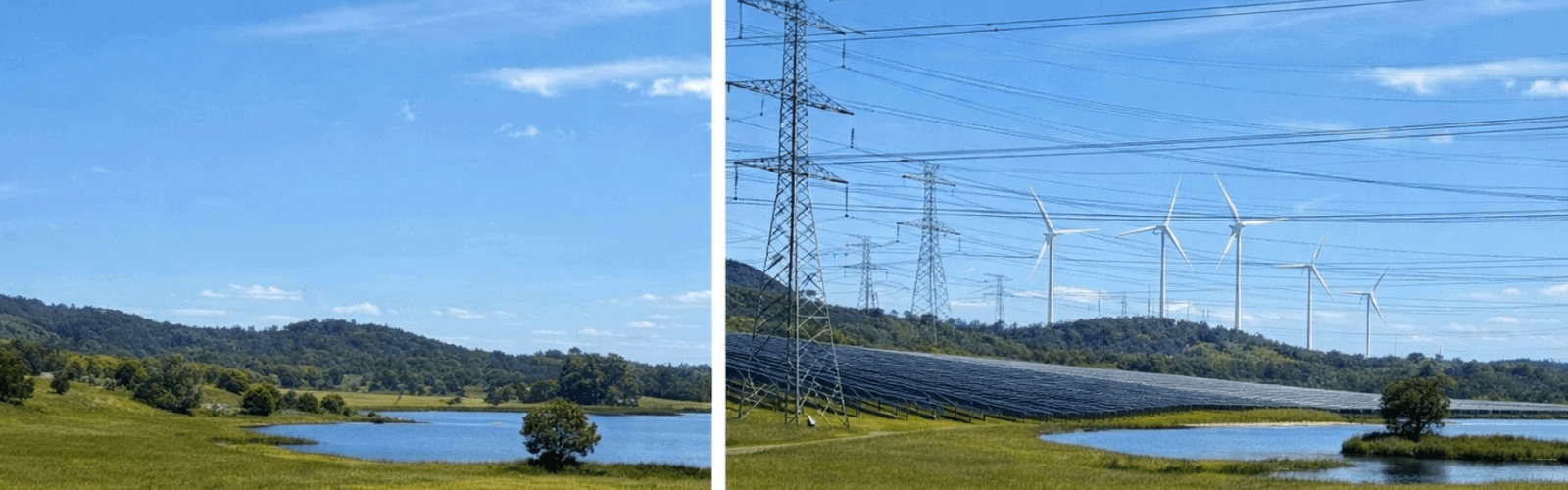

After crossing the Mozambique Channel from Madagascar, Severe Tropical Cyclone Domoina made landfall in southern Mozambique on 28 January 1984, and moved across the border to the Makatini Flats and what was then Swaziland (now known as Eswanti) to dissipate over eastern parts of South Africa. The storm caused 100-year floods in South Africa, reached speeds of 100 km per hour, and bottomed out at 976 hPa.

You know what it's like in a severe storm: pounding down torrents of water, wind howling through the gutters, tipping tables and breaking trees. And then the power goes out, and it stays out for days. And so, it goes.

But imagine the impact on a little hospital far out in the bush. No roads. No telephone communications, no internet, no lab facilities, no stock, no blood.

So, it's torches and candles and the odd paraffin lamp.

It's the aftermath of the storm. I'm sure you can sense there is trouble on the way.

But let me first take you to Maria and the storm proper to get an impression of the impact of water over the Makatini plains.

I don't know how good you are with tracking but imagine coming across this track in the wild. What would you make of it?

Yip, something moved from left to right in the sand with several points of contact. Each point of contact is placed down in succession on the left and then dragged to the right. There are at least three contact points, each with its own pattern: bottom, central, and the third, a squiggly line impacting four times at the top. The latter point of contact is placed down and lifted again with only a slight sideways swipe/drag. The bottom trail has five distinct lines to it, one more prominent than the other and dragged further. The central trail is deeper and dragged more firmly in a straight line. This will be the main point of support. The bottom track is staggered, and the top track swipes to the side, indicating a swaying movement between left and right, independent of the central support structure. If there are any other points of contact/support during movement, it would be placed down ahead of these three points, the pattern brushed over by the three visible elements following behind.

At the end of this tract in the Makatini sands is a lady with polio. Her name is Maria.

Reverent Jannie De Bruin, former Missionary in the Makatini, provided the photos and story of Maria. Thanks Jannie!

Maria is paralysed from her hips down. She moves by dragging her knees forward with her hands, her dead legs flopping behind from side to side. The top of the toes on the right foot pulls through the sands, the big toe impacting most. Only the side of the left foot slams intermittently onto the ground to create the squiggled lines of the top pattern.

Since both hands and knees are occupied in forward movement, we might think she can't do anything useful or even carry anything. We might even pity her, believing her to be infinitely troubled, incapable, and unhappy.

Yet just the opposite is true.

Maria and her equals must be of the most resilient the planet can offer.

And isn't happiness tied to overcoming inequities rather than scoring money or a grand lifestyle?

I'll tell you one of Maria's stories to demonstrate my point.

The flood waters of Domoina rolled over the plains without warning and with great force. After fetching water for the day from nearly half a kilometre away, Maria was sitting in front of her hut crushing mealies to maize with a pestle in a large wooden mortar or "stamp block", when the wall of water appeared. It picked up her hut as part of its angry rubble, grabbed Maria off the threshing floor and rolled her along in the fury. Maria can't swim, her legs a detrimental drag. She grabbed the mortar in both arms and held on for life while being smashed by the torrent. Finally, the grip of the preceding water wall eased, and she popped up in the wake behind, still clinging to the mortar. After being dragged down the Pongola River for about 10 km, her mortar slammed into a tree on the flood plains. So, Maria abandoned the mortar and pulled herself into the tree with her arms, settling for a branch clear of the flood waters. She shuffled, balanced, shuffled again and then settled as the sun dipped into the sea of waters towards the west. It would be a long night clinging to the swaying tree, hit by rubble and logs, listening to the bellowing of hippos above the roar of the waters. She eased higher up the tree and settled into a fork for the night.

At long last, the day came back with light and warmth.

The endless waters around slowly slip into form. No land was in sight.

The tree still sternly resisted the floods. Maria looked up at the top of the tree, swaying against the clear skies, then she felt a shiver in the tree. She looked down. Below her, wedged in a fork, was her elderly mother. She lived not far from Maria and arrived by log in the small hours of the morning, climbing the same tree as Maria in the dark. Both were unaware of each other.

So, they chatted from branch to branch, and had a little chuckle like mums and daughters do when they haven't seen each other for a while. And then they became silent again, looking over the vast waters over the plains.

What happens when the tree gives way?

Where is land, and how do they get there?

The day drifted into night and back into day again. And then they heard the woof woof woof of helicopter blades. We tend to think of angels as having wings like doves, but surely, some angels have rotor blades instead! The crew on board a South African army helicopter spotted them in the tree and hoisted them to safety. And when the waters receded, they rebuilt their huts and planted crops as before, chatting about the great storm and the waters that covered the earth.

At ground level, comparisons are notoriously unfair, and pity diminishes self-esteem and resolve. It might even jeopardise our chances of survival.

When will we ever learn to replace pity with appreciation and comparison with unconditional admiration, reaching a hand of help when needed but forfeiting our selfish merits?

Domoina dumped 950 mm of water (unofficially up to 3000 mm recorded), flooding 29 river basins. Houses, crops, roads, and bridges were swept away, and 242 deaths were recorded. The Pongola River altered its course over the great plains..

And now I'll take you back to Manguzi Hospital.

It was a Sunday night. I opened the door to a soft knock. The nurse held a paraffin lamp to push some of the darkness away. In an equally soft voice, she told the problem.

And she was correct. No blood pressure was recordable, no pulse palpable, and no foetal heart could be detected. The heart sounds inaudible. The abdomen was large and rigid. The patient was unconscious, and only a flicker of movement indicated she was still alive.

Marcia was 36 years of age and lived near Muzi, not too far from the hospital. She had two prior caesarean sections due to a small pelvis, and this pregnancy was near full term. She had been in labour for three days but could not reach the hospital due to the floods. The family knew she was dying and somehow found a way through the waters tonight.

It was clear that Marcia had a uterus rupture. Towards the end of pregnancy, the lower segment of the uterus, where the previous caesarean sections were done, becomes paper thin. Best practice is to do the next caesarean section before she goes into labour to prevent the old scar from tearing open. However, this was not possible. The obstructed labour went on for three days; the uterus ruptured, and she was bleeding free into the abdominal cavity. First, the baby died, and now Marcia's life was balanced on the edge.

Marcia needed blood and an immediate hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) to stop the bleeding.

I slipped a cannula into a collapsed vein and asked the nurse: "I know we don't have blood, but do we perhaps have a unit of plasma somewhere?"

"No doctor, only normal saline," she said and handed me a unit.

We started the intravenous infusion and wheeled Marcia on a trolley to the theatre.

An infusion of a couple of litres of saline would be of little help and provide only temporary relief. Still, it might buy us 30 or even 60 minutes.

My oldest brother, Gysbert, is a great guy. He takes life very seriously, but if he puts his mind to something, he makes it work. And he is clever. When we were young, I saved up some birthday money from Aunt Ida, my godmother, and bought the parts and plans to build a canoe. The dream was to canoe the lake in the middle of the Pilanesberg volcano. But I could barely read, and the plans seemed complicated far beyond my reach. So, I took it to Gys.

He carefully looked at the papers, parts, screws, and bits and finally said, "I think it's doable."

So, Gys built the canoe while I looked on offering a hand here and there.

But as I said, my brother is very clever. He earned himself 50% shares in what was now our canoe!

So, when Hannelie and I decided to go to Manguzi, I phoned Gys, who was working under Sam Phearson at Madunsa Hospital in the north of South Africa. I told him about the virtues of the Makatini plains. I told him about the quaint little Manguzi hospital, the gentle people, the lakes, the rain forests, and the coral reefs. And, as I hoped, the picture was so convincing that he resigned and joined me on the plains with his family.

We have been working together at Manguzi Hospital for a good year now. As we pushed Marcia into theatre, I thought to myself: What would I have done without Gys?

Gys stooped over his thick surgery handbook, sitting on a highchair at a bench in the theatre. A paraffin lamp and candle laid a soft light over the pages. He followed some of the lines with his finger, mumbled to himself and made marks in the book with a pen. Gys has never done a hysterectomy before, but he was good with his hands, has done some excellent surgery, and, as I said, he is clever.

If anyone could save Marcia, it would be Gys.

I eased a whisper of gas out of the anaesthetic machine and into her lungs with the Ambu Bag, put my index finger on the carotid artery in the neck and recorded a faint heartbeat of 120 beats per minute. This central pulse, her pupils, the paled-out mucous membranes and the easing of air in and out of her lungs are the only vital signs to go on for the duration of the anaesthetic. No monitors were working. No blood pressure was recordable. The heart sounds practically inaudible. I would have to ventilate her by hand.

"You can start," I said and looked at the team. Gys and his nurse assistant were scrubbed, gloved, capped, and gowned. Three candles were on the bench, and two nurses bent over with paraffin lamps from the left and right foot of the table. I had the privilege of a dedicated lamp on the anaesthetic machine to keep me on tract.

It was dead quiet when Gys made his first cut.

More than two litres of blood poured out of the abdominal cavity and was sucked up with a manual foot pump. Gys worked quickly, reached the uterine arteries within three minutes, and clamped them off to stop the bleeding. The sudden pressure drops in the abdominal cavity dropped Marcia's blood pressure even further, and the carotid pulse disappeared under my fingers.

"Is there any pulse palpable in the abdominal aorta?" I asked anxiously.

Gys put his tools down, placed his fingers on the aorta, and bowed his head in concentration. After a long while, he said: "Yes, there is still a slight irregular pulse in the aorta."

We had our backs against the wall. No one said a word. Marcia could have a cardiac arrest at any moment.

My blood group is O-positive and can be used to donate to positive blood types but not negative ones. We did not know Marcia's blood group then, and no cross-matching facilities were available. I decided to take a chance. I asked a nurse to help ventilate Marcia and donated one unit of my blood in a bag. I drew 10 ml out of the bag and slowly injected small test volumes of the blood into Marcia's bloodstream.

No reaction detected.

I quickly gave her the full blood transfusion and followed it with a second unit.

Marcia's mucous membranes changed to a faint pink, her wrist pulse became palpable, and I recorded the first blood pressure for the night.

Gys completed the hysterectomy with no complications.

Three weeks later, Marcia was discharged back home to Muzi. She had no baby to strap onto her back and could never bear children again.

But the precious spark of life candled in her eyes again.

The flood waters slowly eased from the plains into the Pongola. They joined the waters of the Usutu River from the West to cascade down the great Rio Maputo. At Maputo Bay, the brown flood clouds swirled into the Indian Ocean like a giant hand reaching from Africa out to the drift-away child of Madagascar, where Domoina was born.

A ringneck dove landed on a branch above the garden table where we were drinking morning tea. He had a fresh Albizia leaf in his beak.

And then we knew that the floodwaters were almost gone.

NEXT TIME:

a dog in the fog

The Song of Tap

an ode to the senses

Not a subscriber yet?

Click here to subscribe - it's free

.svg)

.svg)