The pitch of the engine noise rose to a crescendo as the plane went into a dive, roaring over the hospital, sending dental syringes clattering on the steel tray.

"I hope that plane doesn't drop bombs!" I said and looked warily at John, the doctor. The civil war in Mozambique between the Renamo and Frelimo forces had been raging since 1977, and you could often hear the mortar bombs and gunfire in the evening quiet from across the border.

"No, that's John, the pilot, coming to pick you up for the clinic at Zama Zama," John, the doctor, said with his ever-enduring broad smile. "I hope your dental skills are well polished. You'll have a big dental clinic this afternoon. Could be as many as fifty patients with toothache. Are you good with pulling teeth?"

"The only tooth I ever pulled was that of my little brother, slamming down the door handle with a cotton thread tied to his milk tooth,” I offered.

"I don't think that will cut it," he replied, capping the two tips of his smile with more wrinkles.

"Didn't they teach you properly at medical school?"

Was there a subtle mock in the voice of this scholar from the North? I studied in the South.

"Nope," I said politely. "Teeth weren't part of the deal."

"We better be quick then," he said, rolling the instruments across the table. "Do you remember the anatomical positions of the mouth's palatine, lingual and mandibular nerves? You place a nerve block with 0.1 to 0.3 mL of xylocaine where the nerve emerges from bone. Place a ring block around the tooth if this does not work well. These instruments are for the upper molars, those for the lower molars, those for the upper pre-molars, and those over there for the lower pre-molars. Oh, yes, you use these for the incisors—top and bottom. If you forget what I said, use these, they work for everything!"

He rolled up the instruments, placed them in a box and handed them to Sister Dlamini.

"Sr Dlamini and one late discharge will fly with you today."

And that's it. Lesson over.

As we walked down the dusty footpath, I recapped the lecture in dentistry. Two things stuck well in my head: "If you can't find the nerve or your nerve block failed, infiltrate around the tooth. If you forgot what instruments to use, use this one. It works for everything" The defaults sounded really easy!

We stopped to wait for two drowsy cows to drift across the footpath, and then the Cessna appeared, parked under a forest mahogany tree. John, the pilot, was leaning against the cockpit. When we reached him, he perked up and offered a kind handshake sending his stalky black hair into a shiver. I immediately liked John. He had an open, friendly, honest face with sparkles sizzling in both eyes. Mum used to push my fringe back over my head, saying: "You must have an open face, my boy, so that people can see who you are and what you are up to".

John fitted that bill perfectly, and I could see he was up to flying!

We pushed the tailwheel of the Cessna 195 down the decline and a little to the left, positioning the nose facing towards a break between the trees.

Who would have thought this could become an airfield? I thought, but asked instead: "Shall I go and chase the goats and cows out of the way for take-off?"

"No need for that, lad!" John declared with his back to the strip, fiddling with the door handle. "When we start rolling, the goats will move out of the way, and we should be in the air before we get to the cows", he explained.

And that is indeed how it happened.

As we taxied, bouncing over the crisscross of cattle tracks and small bushes, hurtling towards the goats, they scattered into the scrub. We then hit smooth air and skimmed over the cows that kept grazing peacefully, not flinching as the flying machine soared over their backs into the tropical skies. We banked to the left as Manguzi Hospital disappeared between the trees of the coastal forests, and the skies opened up over the vast grasslands towards the mountains in the west.

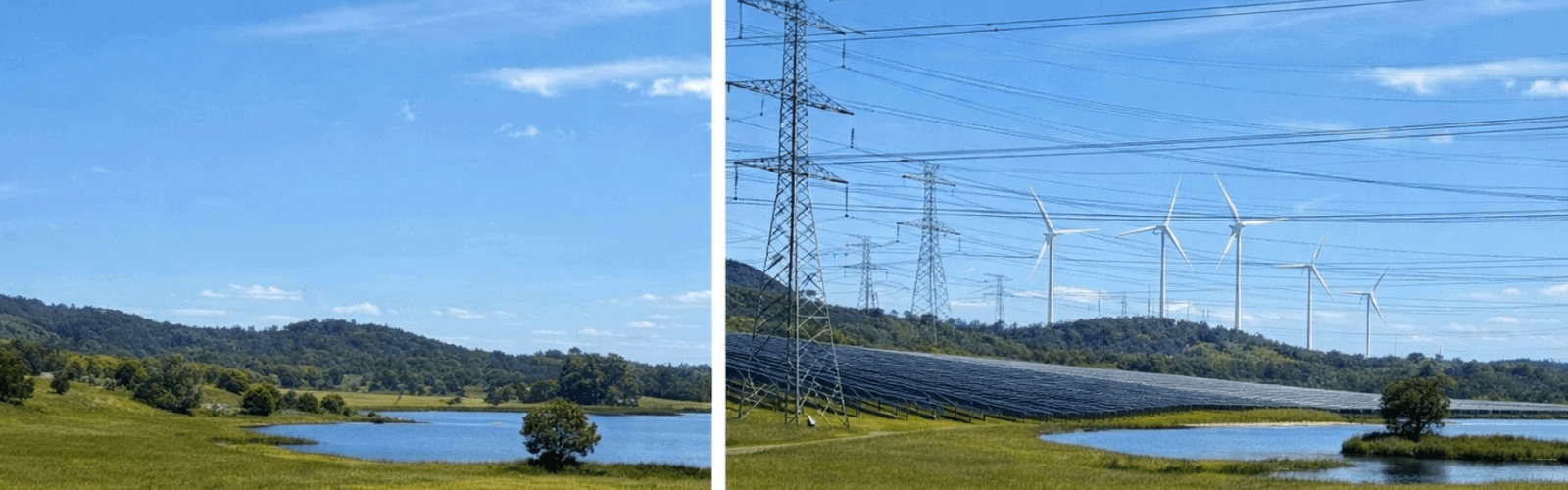

The sand plains of the Makatini in Northern Natal cover an area of 400 000 hectares and lie between the Indian Ocean to the east, the Lebombo mountains to the west, the Mozambique border in the north and the Mkuzi River in the South. Zama Zama, where we were heading, is a small settlement on the banks of the Pongola flood plains, as the river meanders its way across the plains to join the Maputo River on the Mozambique border. The convoy of 4x4 trucks and land rovers had left at 4 am, filled to the brim with discharged patients, staff and all the gear needed to service the more than 200 patients expected at the clinic. The going was slow and arduous, travelling through thick sands, tracking each other as they compacted the road. The staff were dedicated to a 16-hour day, not expecting to reach the hospital again before 8 pm that night. And this hard going on the plains was why the mission in Ubombo on the Mkuzi River supplied the free service of a four-seater Cessna. John, the pilot, transported doctors, staff and patients on a needs basis from the three remote hospitals in the Makatini: Manguzi, Mseleni and Mosvold at Ingwavuma on the slopes of the Lebombo mountains.

"We're nearly there," John announced over the headset and banked steeply. We descended, pushing the revs to 2500 RPM, and skimmed over the clinic to alert a 4x4 pick-up from the riverbank. John did two circuits, surveying the flood plain below, judging the water level, the soil moisture and the whereabouts of people and animals. He then landed us neatly over the tip of an anthill and came to rest under the massive, shady arms of a fever tree on the water's edge.

The three-room clinic building was planked-up and nailed from raw forest timber. The empty shell was furnished and equipped from the convoy cargo for the day. The paediatric nurse running the children's clinic was in front of the building, under a large Albizia tree. A junior nurse used the first room to record observations and perform basic urine and blood tests, while a male nurse ran the second room for general adult medicine. I was doing obstetrics and gynaecology in the third room and overseeing all problem cases from the other clinics.

All went just too smoothly for my comfort.

"Where are the dental patients?" I asked the nurse doing observations and side-room tests.

"They will come", she assured me and looked through the window at the dense forest wall. "They will come out of the forest on the footpath over there, " she said, pointing toward a large Ficus tree with a wrinkled belly and numerous contorted arms and legs. The tree looked old and wise and full of forest secrets.

"What time will they come?" I asked and looked at my watch. The short arm was hanging around three, and the long arm was racing towards 12.

She pulled her lower lip with a finger and muttered: "They'll be coming soon now—maybe at 3.30."

"But the plane will be coming over at 4 pm!" I protested.

"How many patients will attend?"

"There won't be too many today," she said calmly. "Only about 20, or perhaps 30".

I did a quick calculation in my head. With at least one or two rotten teeth per patient, I will have to inject and extract teeth at 30-60 seconds per tooth!

How on earth did John the doctor manage to do this? Even if you know exactly where to inject and what forceps to use, this must be impossible!

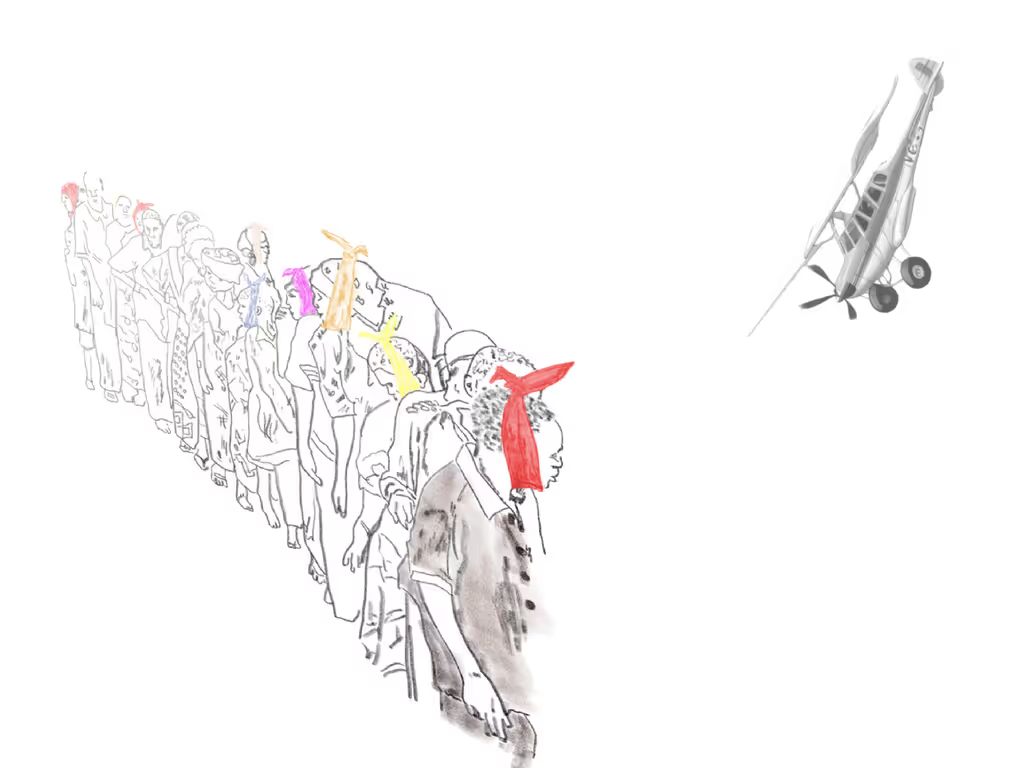

I wiped the sweat out of my eyes as the queue warily emerged at precisely 3.30 pm from the depth of the forest behind the now-smiling Ficus tree. He winked at me with his large, wrinkled brow, burying one wise eye behind the folds of his face.

The first patient had a red cloth wrapped tightly around his jaw and head with a knot tied to keep pressure on his aching tooth. I thought it must be helping with the pain, because the second and the third have done the same. Every jaw was marked with a colourful cloth representing at least 30 aching teeth as the queue snaked along the footpath towards me!

I was ready. Three at a time in the side room, sitting next to each other on the bench in front of the window. The door closed so the rest of the queue couldn't see the gruesome details. The nurse would pass the three pre-loaded syringes one by one to finish the anaesthetic round and disinfect instruments between patients on the extraction round. But one tooth per patient only! They just need to point at the culprit and consider it done.

I identified the nerve, administered the block for the first patient and moved on to numbers two and three, giving the local anaesthetic a brief chance to work. I was back at number one. The only instrument on the table was the default extraction forceps that was supposed to fit all.

It was a large molar tooth in the bottom jaw.

I applied the forceps and pulled.

The patient gave a loud yell and rose to his feet. I apologised, injected again around the tooth and moved to number two. The same story. Then number three. Still the same.

I was getting worried.

A head with a yellow cloth around it peeped wide-eyed through the window, followed by a second and a third.

I was back at number one.

"Just a quick pull, and it's all over", I assured with a smile.

The second round of yelling was worse than the first.

"Don't worry!" I said. "Just a quick pull, and it's all over!" But it wasn't.

I found myself standing on a chair, pulling the tooth towards the ceiling with all I have. The wide-eyed patient stretched to the max before me, standing on the tips of his toes.

The faces in the window disappeared.

I gave up, apologised profusely and picked the tin with Xylocaine up from the table. It was still in date.

It was all my fault.

This is the worst job in the world, I thought; cleared my throat, braved up and opened the door to address the crowds. Only, there was no crowd. I was just in time to see the last figure with a green cloth tightly wrapped around the head, disappearing back into the forest.

The big fat Ficus grinned at me and said: "I told you so. You reckon you're so clever, hey? How is that for the clever city doc!"

And then he frowned a deep Ficus furrow and "comforted" me as an after-thought: "Don't look so worried! They'll be all back next week to see a proper doc that knows what he is doing."

The nurse avoided my eyes and quietly packed the instruments into the box, ready to load it back onto the truck. She then pulled her lower lip with a finger, looked at the floor, and, without a word, disappeared around the corner.

How is it that Dad was so good with teeth? There was not a tooth or a root in the world that he could not extract. But Dad believed that no staff at the clinics (and they visited many clinics around Saulspoort in the Pilanesberg mountains) should be doing nothing. So, he taught Harris, the ambulance driver, to inject and pull teeth. And Harris became an expert at the job!

As sure as that old Ficus tree guarding the forest tract is real, I could have done with a few lessons from Harris!

We took the back seat behind the pilot out and eased the stretcher feet first into the luggage area and vacant seat space. We then hung the saline drip secure on a purpose-made hook in the fuselage of the Cessna. The young man was semi-conscious and thought to have cerebral malaria.

I turned to John, the pilot, with my back to the plane for a confidential discussion.

"What is the payload of your plane John?" I asked in a low-toned voice.

John looked briefly over my shoulder at the triple-size sister whose turn it was to fly out by plane.

"It does not matter, Gabriël. We'll work it out."

"John, just tell me the payload, and we will discuss it ourselves. I don't mind going back with the convoy if need be."

His answer was ready: "It is called discrimination, Gabriël", he said, "and I won't be part of it."

"You can call it what you like, John, but you can't fly an overloaded plane out of this bush!"

The discussion was getting heated, and the sister looked inquisitively at us.

John looked down in thought and then back up again. "Gabriël, let's just get in the plane. I'll work it out," he said in a gentle voice.

So, we pushed the Cessna backwards until it sat on the anthill, pointed its nose at the fever tree and climbed into the cockpit.

John, the pilot, always prayed before a flight.

So, he asked God to look after the patient with cerebral malaria and the people of Zama Zama. And then he asked God to hold the plane in the palm of His hand and to provide for a safe flight home.

I was wondering what God thought about the last request. I thought we are supposed to use all the common sense He provided us with and ask Him to provide for the rest when we run out of luck.

But then, the discrimination business is a significant stumbling block for John...

So, I asked God on the quiet not to be too hard on John for violating common sense and vital aviation principles because he genuinely cared about people.

"Amen," John said, his voice suddenly loud, wiping the sweat out of his eyes with his wet forearm. He pulled the handbrake as tight as it would go, started the engine and set the throttle to max. The little plane shuddered and buried the forest in swirling dust clouds.

Then John dropped the break, and the run started.

The surface of the strip was cracked, dry clay and provided a remarkably smooth run over the short strip towards the fever tree on the water's edge. The long leafy arms of the tree stretched far out over the water, providing shade to half a dozen Egyptian geese cruising around in tight circles, grunting in the direction of the plane. Above their heads, countless yellow weaver birds nested. The crafty little flyers fluttered and chirped between their nests. Their neatly woven grass homes are suspended from the branches above by half a metre of braided grass to help deter snakes from reaching their young.

We leaned over the dashboard, eyes nailed on the massive tree, hoping and praying for a lift.

But the plane had led in her tyres. The tree grew more enormous in the windscreen by the second.

Finally, long after the abort take-off point, the frame stopped shaking, and we drifted into air. The top of the tree disappeared. John tilted his head sideways over the dashboard to regain perspective, his white knuckles pulling the stick further and further back to assist. Instead of accelerating, the airspeed needle started to drop. In a futile effort to clear the tree, John kept pulling the stick backwards, forcing the nose further up. The stall alarm sounded, mixing its haunting honks with the engine's roar.

We were far behind the power curve. The airspeed was close to zero. At any moment now, the plane would fall backwards to the ground.

The next moment John slammed the stick forward, and the nose dropped off a cliff. We dived near vertical towards the ground in front of the fever tree; the engine revs building up to a crescendo in seconds. Before we hit the ground, John pulled the stick back with all his force and banked sharply right to avoid impact with the tree. We skimmed over ground and then water, but we were under the tree before he could level the wings. The right wing plunged through the geese, and the left wing sliced through the bird nests.

The plane emerged on the other side of the fever tree in a swirl of leaves, feathers and grass.

John levelled the plane's wings over the open waters of the Pongola floodplain and started a slow, steady climb with his non-discriminating, far-over-limit load still on board.

"Do you guys always fly like this?"

It was the sister speaking from the seat behind me.

A very long stretch of silence followed.

Finally, John, the pilot, answered, his voice in complete control: "No, Sister, not usually. We only fly like this under extraordinary circumstances."

“A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defence of custom. But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason.”

- Thomas Paine

How tall we stand in eyes that behold

yet how small in the pledge of time

How great the works of hero’s

yet how brittle the resolve

Please give your opinion on Audio versions of the stories HERE

NEXT TIME:

The great ships passing around the Southern Tip of Africa was controlled by Soliman - but perhaps not in the way you expect it would happen.

I’ll take you to his control centre if you dare to come along…

The Song of Tap

an ode to the senses

Not a subscriber yet?

Click here to subscribe - it's free

.svg)

.svg)