The brunt of the Closing the Gap program was placed on GPs, and we sadly failed.

I’ll take you into the country as we try to understand how it works, avoiding politics as far as possible.

Much is broken on both sides.

In fact, my hope is on the Old People of the Land to bring a runaway nation back into the fold.

It is a Saturday in Spring, and the venue is on a hill in Mission Beach, Tropical North Queensland. The green islands float below on silk, and the azure wrapping cradles the chalky sands, offering little handshakes of frothy waves to the beach. Why did I ever agree to a medical conference on a day like this?

Someone rings a bell, and another starts ushering us out of our dreams and into the reality of a lecture room. Life is not fair!

In the room is a doctor-facilitator, a medical rep from so-and-so company and about 25 doctors in the same boat as I. The topic is the new release by the company of blood sugar and blood pressure machines that patients will use to monitor their own progress on prescribed medications. The discussions go something like this:

“So, we are going to teach the patients to become independent and no longer require our services anymore?!” one says in alarm.

“They always get it wrong; they’ll be back to ask for advice!” someone answers.

“Yes,” another added, “you can give them Google, AI and all the gear in the world; they’ll always come back because they need us”.

“Not true!” another differs, “There is a point of knowledge saturation. If the patients have reached this point, they will be self-sufficient, and we will become redundant!”

“We will never be redundant!” a voice concluded, “It’s like moths around a candle. We have the magic!”

Everybody laughed.

I once tuned the engine of an old Ford F250, but accidentally set the timing 180 degrees out. When I turned the key, it was like a rocket attack! Instead of the pistons driving the crankshaft out of a closed cylinder, all the fire and smoke exploded through the open carburettor into the innocent Sunday morning air!

So, I said: “I think our premise is fundamentally wrong, thus our fear of survival. The patient does not approach our halo of wisdom because we hold the beginning and end of knowledge. The opposite is true. It is a privilege if a patient would choose to consult with us, allow us into his private world, talk about his hardships and experiences and, if he trusts us, perhaps even allow an opportunity to influence him. If we then provide some knowledge and wisdom needed to assist in health and wellbeing, we have reached our goal. Survival for us then does not need to be a target. It will be auto generated by a friend.”

All turned to look at me in disbelief. The facilitator dropped his jaw, and the rep smiled quaintly, looking over her audience. But no one said a word.

As doctors and health providers, we move around in a paradigm imposed by layers of authority, including academic institutions, government bodies, accreditation bodies, insurers, and registration bodies. This dictates what we say and do and how we say and do it.

These structures are needed to ensure a minimum efficiency standard and to safeguard the public against exploitation. Still, it imposes a top-down approach that is often insensitive and disrespectful and can easily be exclusive and counter-productive. It can even cost lives, limit life expectancy, and (as we will see) does nothing to “Close the Gap”. No wonder we need indemnity forms signed to safeguard us from prosecution!

There is a dichotomy in health care that cuts to the heart. A principle of access overlooked. Greater than my bequest to deliver is the quest of you, my patient, to first consider placing the order and then to screen the delivery. We need a new heart.

Let’s now go to a small rural and remote village in Queensland to see how it all started. We will call it “Fair-Go Village”. It is the year 2008. The community has a sizeable Indigenous component, only one surgery and one doctor in town. Me. In response to the social justice report by the Social Justice Commissioner Tom Calma, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), under Kevin Rudd, approved the National Indigenous Reform Agreement. Six Closing the Gap targets were set out, most notably closing the life expectancy gap within a generation. A well-funded MBS item number for “Indigenous health checks” was created to be used in conjunction with Chronic Disease Item Numbers and other incentives. The pressure was on GPs to produce measurable, good looking results for the government.

An email landed in my inbox from a practice manager in a nearby town. It read something to this effect: “Dear Doctor, this is just a courtesy email to inform you that our local Aboriginal Health Organisation will open a surgery in Fair-Go Village. We will supply culturally appropriate health services to the Indigenous community, targeting Closing the Gap”.

There was a phone number and a name provided for enquiries.

The phone discussion had this ring (I did most of the talking): “Sir, our Indigenous patients are part of the family in this practice. We are proud to have them as part of our operation. We also have an Indigenous health worker who regularly does home visits and works closely with the surgery team. A separate practice will create tension in the community, forcing them to choose between our practice, which they love, and an Indigenous-specific one."

He was not persuaded, and I tried again: “Sir, we have enough stress in town. Please talk to the local Indigenous people. If I am wrong, go ahead and set up the surgery. If I am correct, you are welcome to free space in my surgery to set up whatever you think is culturally appropriate. We can deliver services as a united team to the community; it will not create tension, and we will have a better chance of success.”

The refusal was firm. The Aboriginal Health Organisation opened an Indigenous Clinic at the other end of town, forcing the community to choose. The clinic employed a full-time doctor, nurse, and health worker. The doctor serviced one to two patients per week and finally reiterated my concerns to management. The doctor was sacked and replaced by another doctor who did not question anything and kept reading his books quietly. After substantial losses, the clinic closed a year later.

But for me and my team, this introduced a sad period.

There was a change in our attitude as service providers towards our Indigenous patients. We started imposing bureaucratic box ticking and form filling while placing pressure on compliance and reporting on compliance. The quality-of-service delivery worsened, since it took away valuable, intuitive consultation time in favour of an agenda.

The rules did nothing to create or improve an unconditional relationship of trust and respect. If anything, it undermined it. The community became more stressed, divided, and confused. In their eyes, we became government agents exerting pressure, measuring compliance, and reporting to the government with who knows what consequences to them.

And then there was the unfortunate choice between a loyalty to their Indigenous race and an adherence to our services that the rest of the community supported. Although they chose to keep supporting our services, the ambivalence came at a price.

Sadly, the same stress to choose is happening on a national scale again.

It soon became apparent that the initiatives would do nothing to “Close the Gap” in our and similar settings. In fact, it might even contribute to widening the “Gap” and, as a spin-off, introduce more mistrust at a grassroots level.

The cost of the project?

According to the 2012 Indigenous Expenditure Report by the Productivity Commission, the “total direct Indigenous expenditure was estimated at $25.4 billion.”

So, please venture with me as we try to unpack the problem to better understand the issues. Note that I am no anthropologist, nor an expert in this field, merely someone concerned, trying to understand what I see.

My first question: Where did this “Gap” come from?

There was no gap 1000 years ago. Life expectancy was much less than now, but no one worried. The answer is simple but important: “The Gap” only appeared when the settlers arrived. It is an expression of comparison.

This is, in principle, a shaky foundation. Comparing people can lead to adverse outcomes such as discrimination, judgment, or the unfair treatment of individuals. It can perpetuate harmful stereotypes, foster a sense of superiority in some and inferiority in others, and disregard the uniqueness and individuality of each person. It’s essential to recognise that everyone is different and has their own strengths, weaknesses, and life experiences. Instead of comparing, it is often more productive and respectful to appreciate and celebrate the diversity and talents that each person brings to the table.

When motivating to Close the Gap in Australia, Tom Calma points out the multiple disadvantages of Indigenous Australians compared to their new peers. He refers to Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the right to the highest attainable standard of health of the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. In Australia, the overall gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians is nine years. This compares to fifteen years in Canada, eight years for Native Americans and four years for African Americans compared to their white counterparts.

So, we are competing in the international race to close the gaps, reach zero emissions in 2050, and standardise whatever else needs standardising. In Australia, we are in the final grand attempt to abolish the gap and score international gold!

My second question: How would I feel if my comparatively “poor performance” had been elevated to this level?

How would I feel about the inherent pressure exerted on me and my people as a result?

It is indeed admirable to be concerned about and help those in need. Even more so if it comes at a cost of money, infrastructure and expertise sourced from the wider community. However, support needs to be born out of genuine concern, not delivered with a paternalistic attitude and point scoring on a second agenda. And even more importantly, the recipients of my aid need to believe that.

My third question is perhaps the most important of all. If we take the international pressure, all the money, the charged politics, the over-zealous media, and all the hype out of the issue—what is left?

We are left with a 65,000-year-old people who lost their country and identity and are dealt an intricate hand and bruised spirit. The settlers arrived with boats, weapons, and technology far superior to what they had ever encountered. The land was indefensible.

And nearly every encounter after would picture them as an inferior race: unable to read or write, no factories, no laboratories, and no vehicles. The lack of immunisations, lab-generated medications and access to surgery was implicated in a high infant mortality rate and short life expectancy. And comparative social behaviour was often regarded as unacceptable and even savage.

So, we started imposing the ways of the “superior” race and identified ways to exert pressure while measuring the progress of assimilation or “uplifting”: jail occupancy rates, literacy and numeracy, education levels, infant mortality rate, life expectancy gap, etc. But the jails keep getting fuller, the drug and alcohol problems more significant, “Closing the Gap” as elusive as ever.

My fourth and final question: Is there a way to reach the searching hands on the other side of the divide?

And the answer is unconditional: “Yes!”

How do I know that? Because I saw the top-down approach fail under my hands. I saw my relationships with my patients dwindle to bare necessities under the “Closing the Gap” program. But I’ve also experienced the bottom-up approach. And because it’s built on respect and humanity, it works.

Here it is again:

“Greater than my bequest to deliver is the quest of you, my patient, to first consider placing the order and then to screen the delivery. We need a new heart."

The first principle is respect and the acceptance of equality as human beings. It is unconditional. It does not measure, and it does not compare. It is something needed in the social fabric of a nation. And it is already happening out there, in the country and even in the cities. We just need much, much more of it!

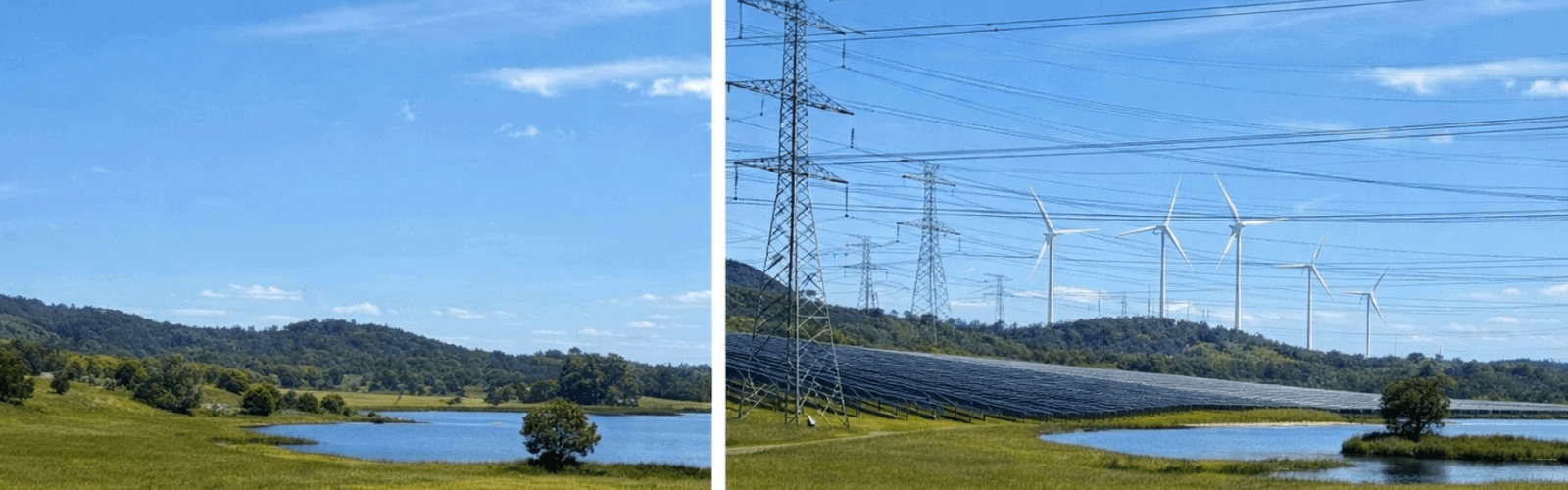

Also: claiming the technological high ground does not imply possessing the moral high ground. We have our own moral challenges to overcome: euthanasia, abortions, gender confusion, renewables choking the countryside, and many more. We have many reasons to remain humble.

Dear reader, it is time to reconsider our attitude towards the people of the First Nations of Australia. We have the privilege of sharing space and land with an ancient culture. Why don’t we listen before we talk, learn before we teach, and appreciate before we judge?

We might find ourselves helping to heal and being healed ourselves.

In a river of a thousand generations, ten is but a drop. If we return to our humanity, we might soon find the jails empty and the gap void because friends walk lightly and share their burdens with smiles. We are not the same people, but we ought to carry the same heart.

NEXT TIME:

Domoina

profound but beautiful

Part 2 of the short series on Cyclones plays off in Africa

Although worlds and cultures apart, the human heart holds the same yarn

The Song of Tap

an ode to the senses

Not a subscriber yet?

Click here to subscribe - it's free

.svg)

.svg)