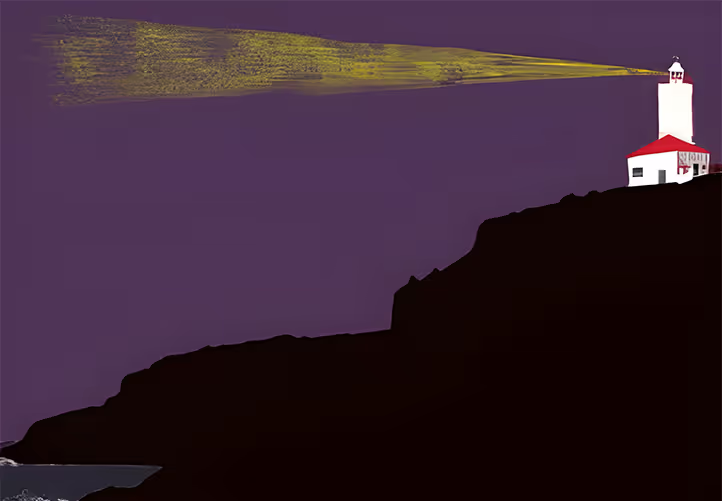

Mossel Bay shelters from the sea on the south coast of South Africa. The seaside of the land spear takes the brunt of the turbulent and unpredictable waters over the edge of the continental shelf, called the Agulhas Bank. The seas carving their story into massive sandstone cliffs tell of the ancient conflict between two converging currents from the east and west coasts of Africa. Many ships wrecked on the reefs in the trade between Europe and the East—their scattered remains translated by nature into framed ecosystems on the floor of the ocean.

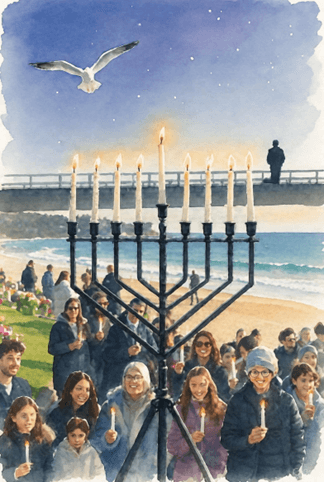

But the leeside of the spear is the tranquil compeer. At Santos Beech, small shiny hills of water glide out of the sleepy bay, shattering on the yellow sands of the cove. Seagulls glide free from the chattering on the beach and the harbourside and soar on invisible winds. If they choose, they’ll skim over the sandstone houses on the hillside, mocking the toil in the gardens and veggie patches with their screeching cries.

Such is the gateway to the Garden Route of the Southern Cape.

On one brave Saturday morning I decided to try and find a way down the cliffs. Many a rock climber has fallen to his death on the rocks far below. But I’d grown up on the rocky ledges of an old volcano in the Bushveld of the north. Rocks comes natural under my feet and heights had lost some of its daunt. Or so I try to assure myself.

The grey seas looked nearly solid from the top of the cliffs—as if carved out of lead. Even the slightly curved horizon had chips knocked out of it. And then I saw it: a huge tanker broke the skyline like a silicon chip on a mother board. I then spotted a second and a third ship—all lined up on a journey to somewhere, but clearly well off the Agulhas Bank into the high seas.

After surveying the rock face for a good while, I found a sequence of cracks and ledges that I reckoned could take me to the bottom. I carefully footed my way down, only to become aware of signs that I was not the first one to follow this route.

A slightly polished rock here and smoothed gravel there. Some broken twigs on a Leucadendron bush. Nearly as if someone was carrying or dragging something down the cliffs!

At the bottom of the cliffs, the round boulders between the waves were covered in black mussels—the bivalves that Mossel Bay was named after. It was low tide. The intertidal zone on the rocks displayed an abundance of resilient sea life that usually manages to survive the onslaught of the seas. That is if there is no storm. Even these tough molluscs and seaweeds can’t withstand the wrath of the high seas on the shoreline in a storm, lining rock pools and high-water lines with decaying sea life covered in a yellow-brown froth. The washing machine of the thundering waves can spill out thick carpets of foam swept up by the winds and driven to shore—often more than a metre in depth!

I rock-hopped for a while along the shoreline and looked over my shoulder. Behind a large rock was the unmistakable opening to a cave!

“Good afternoon, Soli!” I greeted cheerfully.

But Soliman took no notice. He is standing in the doorway staring at the ceiling. His hands and arms swirling around and pointing in various directions in rapid succession.

On my way to the hospital to attend to an emergency, I saw Soliman working his way through the rubbish bins in the street—like I’ve seen him doing many Saturdays before.

“Where is that black plastic bag of yours? Can I have a look at it?” I asked in one sentence.

Soliman reached around the door and pulled a black plastic bag into sight, without removing his eyes from the spot on the ceiling. Again, I tried to see what Soliman is looking at, but all I could see was a flat, white ceiling.

I stood up and opened the bag. Inside were all sorts of papers, from magazines to newspapers. Even children’s drawings and clean sheets of scrap paper. I also noted toilet rolls, empty aerosol cans, broken toys and even an old, rusted typewriter.

“I see you missed your injection during the week. Shall I ask the nurse to give you your needle now?” I asked. Soliman has schizophrenia.

He vaguely nodded his head, his gaze still fixed on the imaginary spot on the ceiling.

“Where do you live Soliman? Do you still live with your sister in Rosebud Street?”

To my surprise the answer came immediately: “No!”

“Why not?” I pushed on.

“They don’t like me anymore.”

His eyes wandered over the ceiling, looking for more imaginary spots. His arms still pointing in all directions.

“I know where you live” I said and watched him closely.

Soli turned to me for the first time and looked me briefly in the eye.

“No, you don’t” he said and looked at the ceiling again.

“You live in the cave down the cliffs. I went to your house the other day, but you were not there”.

He looked at me in astonishment that lasted a few seconds, before he scanned the ceiling again. But I knew I was right.

“I would like to come and visit you again. When can I come?”

For a moment his eyes seem to stop in one place. They narrowed in critical inspection, but then moved on, scanning the blank ceiling.

“I am off next Sunday. Can I come and visit you in the morning?”

“Ten o’clock,” he said without looking in my direction, then took his plastic bag and disappeared through the open door.

“That is one appointment I won’t be missing” I mumbled, looking up at the clear, white ceiling.

It was a fine Sunday morning. One of those days that seems to linger timelessly in its own splendour. It felt like blasphemy to look at my watch. It was ten sharp.

On top of the rock in front of the cave stood Soliman. He had short pants on. No shoes. No shirt. His gaze was fixed on the horizon. He seemed totally unaware of me, and of his surroundings for that matter. His hands and arms swirling around and pointing in various directions in rapid succession.

I assessed the situation for a moment.

“What are you doing Soli?” I shouted above the roar of the waves from behind him.

“Directing the ships!” he called back without interrupting his duties.

“Where are they going?” I shouted again.

“Mainly from South Africa to Australia, but they are going all over the world!” He sounded confident and completely in control of things.

“You missed a boat the other day! It capsized south of the lighthouse.” I thought to challenge.

“I know.” He sounded unperturbed. “I can’t help it. They would not listen to my instructions!”

Soliman's gaze remained fixed on the horizon, his arms pointing in all directions as he coordinated the ships on the high seas to the south of the continent.

Dr Michael, one of my colleagues, had told me about the incident. He was asked to be the medical doctor on board a Sea Rescue boat. They were alerted by EPIRB of a fishing vessel that capsized 60 nautical miles south of the Point Lighthouse in Mossel Bay. They departed before dusk from the Mossel Bay harbour and sailed nearly five hours before they tracked down the boat. No survivors could be found, so they launched four rubber ducks (inflatable rescue boats) to search the surrounding area. Each boat was equipped with GPS and radio to stay in contact with one another and the mother ship. Neither the shore, nor the mothership, nor any of the other rescue craft were in sight when the rescue craft Dr Michael was in came across a Japanese fishing trawler. The fishing trawler slowed down, and all the crew gathered on deck, staring at the rubber duck, drifting seemingly aimlessly around on the open sees. After a while the captain emerged on the deck with a megaphone.

“Lubbe duck! Where ye going Lubbe duck?” the captain demanded from the deck.

The crew on the rubber duck looked at each other.

The Sea Rescue skipper then cupped his hands around his mouth and shouted back at the captain in equal volume: “Were going to Australia!”

Commotion followed on the deck of the trawler and hands were pointing in all directions while they were trying to digest the information. This little inflatable boat with a single outboard motor of no more than 100 horsepower, is apparently on its way to Australia. After a while all seemed to calm down and the captain emerged again with his megaphone delivering his final verdict.

“Lubbe duck. You mad Lubbe duck! Go home!”

It was indeed time to return to the mothership. So, the skipper turned the key, swung the nose north towards the shore and waved at the captain. The whole crew on the Japanese trawler waved back—the clapping of hands echoing over the smooth seas.

After what seemed like a very long time, Soli gave a few last directions and climbed off the rock. I was relieved that the traffic finally subsided (at least for a while) and shared my relief with Soli. A slight hint of appreciation curled around one corner of his mouth, quickly replaced by the serious matters at hand.

We would briefly tour the cave before the next ship’s arrival.

The foyer cave was wide with a high ceiling. The walls were covered with stacks of paper from the floor to the stone roof. Pushed in between layers of paper were plastic toys, toilet rolls and lots of empty aerosol cans. An old broom was positioned against the wall in one place to keep some of the stacks from falling over. The same function was taken up by a broken spear gun against the opposite wall. The ceiling was thick with soot from the fireplace in the middle of the cave. Next to the heap of ashes was a rock for Soli to sit on.

The bedroom walls were of similar make. The only difference were multiple candles positioned on shelves of paper stacks. The candles were clearly in use, with hard wax stalactites gluing the pages together as proof. The back wall of the bedroom had a small hole in the rock, leading to an unused back cave. The hole was framed with paper stacks but clearly supplied much needed cross ventilation.

On the floor was an old coconut fibre mattress with two blankets. Next to the mattress on a rock, stood the old, rusted typewriter.

“Is this where you type up your reports about the shipping traffic?” I asked.

My host nodded in a matter-of-fact way, but I hoped also in appreciation of the insight of his visitor.

“Very good, very good Soli!” I congratulated him warm-heartedly at the end of the tour. “I have only one concern. Those candles and the fire burning in the front cave at night. What happens if all the papers catch fire? You might not be able to get out of the cave in time if this happens.”

But Soli was not impressed with my level of understanding, shook his head, and walked out of the cave.

“Soli, just promise me one thing” I tried again, trailing behind him to the big rock. “Take all the aerosol cans out of the walls. If the cave catches fire, this is going to be like Armageddon with bombs going off all around you!”

But Soli was unaware of my existence.

The first ship arrived again on the horizon. Soli hurried up the big rock disturbed by the fact that he was already a few minutes late with his directions.

Three months passed and I was again on call in the Emergency Department of the hospital. Suddenly Soli appeared in the doorway. At first, I did not recognise him. He was covered in black soot from head to toe. His hair was matted by fire and his eyebrows and eyelashes burnt short. His white eyes flashed momentarily in my direction. There was a burn hole on one side of his pants, and I could see a blister on his thigh.

“Come in Soli” I heard myself say in a sorry voice and stood up from the chair.

“What happened?”

Soli walked slowly up to the table looking down at the floor.

“I made a big mistake. I gave directions to a pirate ship yesterday afternoon and then they knew where I live. They came in during the night, put my cave on fire and attacked me with Armageddon—just as you said. They nearly killed me.”

I directed him to the couch. Soli laid quiet with his eyes closed on the bed, his arms motionless next to his body.

At least for a while, Soli was not going to direct any ships on the high seas to the south of Africa.

NEXT TIME:

Cyclone Yasi in Australia was the biggest storm in Queensland’s history and Cyclone Domoina in Southern Africa caused 100-year flooding

Join me over two episodes on the insides of two vastly different cyclones to watch the people and the fascinating impact of these massive storms

The Song of Tap

an ode to the senses

Not a subscriber yet?

Click here to subscribe - it's free

.svg)

.svg)